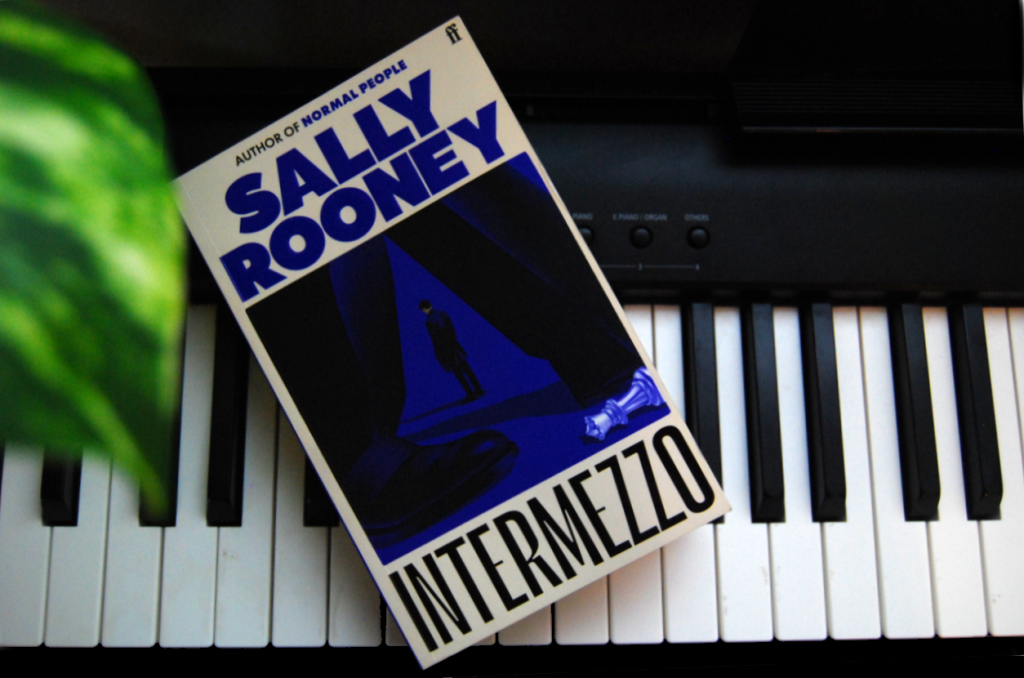

Misreading Sally Rooney: Intermezzo in Focus

We are born, and one day, we cease to exist. If we’re lucky, we get to make a few interesting moves in between. To me, this is what Sally Rooney’s new novel, Intermezzo, is about: the middle game we simply call life.

The book offers a glimpse into the lives of a handful of characters as they navigate universal themes such as loss, grief, friendship, and love. They play their parts, make their moves, and eventually learn to anticipate the actions of others. But before they reach that point, they are confronted with a series of unexpected turns — intermezzi, if you will — that throw them off course. Unable to make premeditated moves, they must improvise to keep the game moving forward.

In the novel, Ivan Koubek, a twenty-two-year-old chess prodigy, embodies this metaphor well. He loves the middle game in chess, explaining that while the opening is rigid and the ending often follows predictable formulas, the middle gives space to creativity. It’s here, in the fluid in-between, that he finds room to make the game his own.

But as Ivan knows, the middle game doesn’t happen in isolation. It depends on the moves of others. And perhaps this is why Rooney’s storytelling feels dynamic despite not being plot driven. But her narrative is also powered not solely by her characters as individuals but by the intricate ways their relationships evolve and shift over time.

In a lecture on James Joyce’s Ulysses (published as Misreading Ulysses, to which my title alludes), Rooney provided a brief history of the novel, focusing on how relationships became central in driving the narrative. She explained that while earlier Anglophone works, such as Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe or Beowulf, centred on characters facing external challenges, this shifted with Jane Austen. In Austen’s work, plots are driven by the development of relationships between characters.

Austen also developed the techniques to sustain reader interest in narratives centred on relationships rather than external events. Rooney — and everyone who came after Austen — inherited these techniques and built on them to the extent of their own genius. Even Ulysses, which succeeded in destabilising the novel as a form, relies on this technique, as it is ultimately relationships that are at stake for Bloom, Stephen, and Molly.

“Every person is intrinsically interesting, but in a novel, what gives a character power is their relation to others, and how those relations change,” Rooney said in an interview with The Paris Review. To her, protagonists come in twos or threes (or fours or fives) rather than separately, and her novels unfold as she explores how these characters relate to each other.

Indeed, in Intermezzo it seems like what matters most is not who the characters are individually, but who they are to each other. The novel is driven primarily by the relationship of two brothers, Peter and Ivan Koubek (the chess prodigy from above), and the women they love. Peter is a thirty-two-year-old barrister who is successful and knows what to say and when. Ivan wishes to be more like him. But they are ten years apart, never liked each other, and are grappling with the loss of their father which makes them both spiral as they try to figure out their next moves.

Rooney writes Ivan and Peter into existence through different narrative styles. Free indirect discourse takes place — that’s also faintly Austenian — to reveal the thoughts and feelings of the characters. But while Ivan’s reflections are more calculated and easier to follow, Peter’s thoughts are jumbled and wrapped in Joycean sentences. Stream-of-consciousness. Inverted, half-sentences. Thoughts jumping around short, choppy lines. Internal chaos. Goes well with his habit of drinking and self-medicating and his tendency to push himself to the edge of a breakdown.

Besides the two brothers, we also get to see the perspective of Margaret, a thirty-six-year-old woman, who runs an arts centre in provincial Ireland, and develops a relationship with Ivan after they meet at a chess event she organised. Similar to that of Ivan’s, Margaret’s point of view is more straightforward and coherent and provides readers with a clearer understanding of the happenings and the emotions involved.

This traditional narrative approach also complements her experience living in a small town, where the social rules and norms are stricter compared to a big city, like Dublin. Margaret is reserved, and worried about how she might be perceived dating a much younger man, while she’s separated from her alcoholic husband. She’s concerned that while her marriage was ruined by her husband’s drinking habits, she would be the one ultimately judged for not doing more, not helping him more, and instead sleeping around with someone who’s at least fourteen years younger than her.

The situation is reversed for Peter, who is dating Naomi, a twenty-three-year-old woman who comes across as shallow and often asks him for money. Despite this, Peter remains deeply fond of her. We learn that Peter views Margaret — and by extension, perhaps himself — as not normal for being in a relationship with someone Ivan’s age. But while Peter admits his hypocrisy and he’s too embarrassed to introduce Naomi to anyone in his family for over a year, his friends don’t seem to have a problem with her age.

He’s a lawyer, he’s successful, he’s a womaniser, and he can have fun. While the double standard seems obvious, Rooney doesn’t dwell on it. We don’t get Naomi’s perspective on the implications of dating an older man. Although Peter briefly acknowledges the inequality that comes with it, while he contemplates Ivan’s relationship with Margaret, for Naomi, it’s sort of implied that because she is Gen Z, she is used to all kinds of unconventional relationships.

You’re twenty-two, you’re hardly out of college, you don’t even have a job. I’m not trying to be disparaging, but do you think a normal woman of her age would want to hang around with someone in your situation?

Sally Rooney

There is one more character whose actions deeply affect both Peter and Ivan: Sylvia. She is Peter’s ex-girlfriend. They are the same age. With her, life was warm and beautiful, and his bond with Ivan was more in harmony under her influence. However, at the age of twenty-five, Sylvia suffered a terrible and mysterious accident that left her in chronic pain and unable to engage in intercourse. While this led Sylvia to break up with Peter, they maintained a platonic relationship over the years, one soaked in sexual tension. Besides mourning his father and agonising over his relationship with Ivan, Peter is lamenting the life he could have had with Sylvia — had the accident not happened, had they stayed together, had she not pushed him away, had Naomi not entered the picture.

Although we don’t get to see Sylvia’s perspective, her character stands out to me. Her interactions with Peter and the way other characters talk about her made me want to know and understand her more. What really happened to her years before? What is she thinking? Once her presence became stronger in the novel, I found myself turning the page because of her. Of course, I was interested in finding out more about her relationship with Peter, even rooting for them occasionally. But frankly, I could easily see myself reading a story that’s entirely about Sylvia.

This made me wonder, is it really their relation to others that gives characters power in a novel, as Rooney pointed out? Or are we interested in the relationships because of the characters involved? I know this almost sounds like the chicken and egg problem. But even though relationships are at stake in Intermezzo, the characters often seem to exist in parallel worlds with stories that can unfold on their own. And when these worlds and stories intersect, it might feel a bit predictable and forced, almost sensing the narrator’s conscious effort to bring them together. What especially gave me this impression is Rooney’s attempt to resolve the novel by bringing Peter and Ivan together, telling us that it is the fraternal relationship that is ultimately at stake. While this resolution was somewhat fulfilling, I was left with several questions regarding each individual character. But perhaps this is where the novel’s genius lies: in its ability to craft characters that grow under your skin and stay with you beyond the pages of the book.