Reading Kate Briggs: Reflections on Motherhood, Narrative, and Time in The Long Form

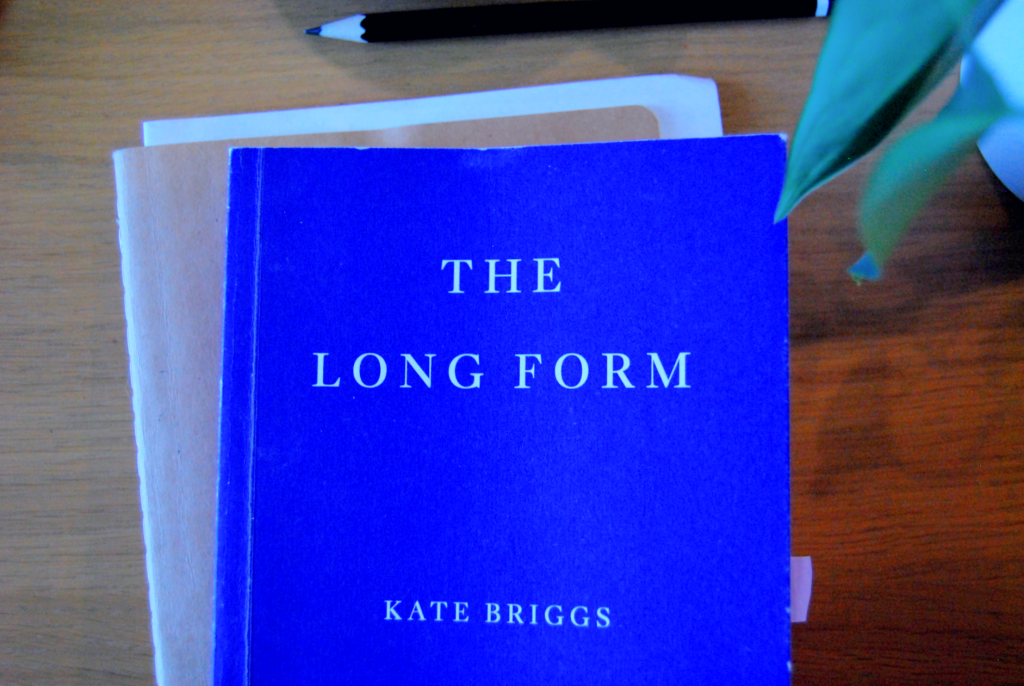

When a book makes me pick up a pencil within its first few pages, I know that I am in for a rich reading experience, which makes me excited to keep turning the pages. My copy of The Long Form by Kate Briggs contains underlined passages, annotations, and sticky notes revealing the impressions it left on me. It was a refreshing read that I’ve taken in in chunks over a roughly two-week period during December’s shortest days.

The Long Form is a multi-layered narrative and achieves many of –– what I consider –– the novel’s purposes: it entertains, educates, pushes us to reflect on our existence, reveals the universal in private histories, and questions itself.

On the surface, the book seems to be about motherhood, or rather the beginning of motherhood, with the narrative unfolding over the course of a day, showcasing the various dynamics between Helen and her six-week-old baby, Rose. As a newborn, Rose is entirely dependent on Helen and this dependency is one of the driving forces of the narrative, creating movement and (non-)rhythm throughout the entire novel.

In the English-language novel, however, babies are never part of the narrative, Briggs pointed out in a podcast with her publisher, The Fitzcarraldo Editions. Babies show up, make an appearance and then fade into the background, only to reappear years later, when they are old enough to be characters with agency.

If this is true, Briggs already disrupts the English novel with its subject matter and also sets the perfect ground for the questioning of the novel’s form and narrative structure, which is ultimately what the book is trying to achieve.

To dissect the novel, Briggs introduces The History of Tom Jones by Henry Fielding, an 18th-century novel that’s occupied with narrative form and structure. Tom Jones inevitably raises questions such as: What makes a novel? Who is seeing and who is speaking in the novel? Can a work concerned with its narrative be called a novel? To what extent does or should real life resemble fiction? Or should the novel just confirm and replicate real life, never to expand on it? (Briggs 229)

With this literary classic, The Long Form becomes a delicate blend of fiction and essay writing: Helen and Rose’s story is continuously completed and contrasted with reflections on the novel as a form.

Helen has consciously chosen a long read. She wanted a “narrative to cut life with.” (Briggs, 100) With a newborn baby, her life is more or less confined to her living room, but a novel allows her to escape life, to escape her confinement. Books also conveniently come with chapter breaks, which “help root novels in the routines of everyday life.” (Briggs 332)

Throughout the day, Helen slips seamlessly into the realm of the narrative and then back into her life, attending to her duties as a mother. Because “it’s possible to put down a novel (face-down) on the carpet. To leave it there and forget about it. To attend to all manner of other things and make it wait.” (Briggs 253) But this constant switching between the realms leads to a collapse of temporal order, in which the lines between clock-time and the lived experience (intensity) of time are constantly blurred.

In the chapter titled “The Time Arts,” Helen imagines herself attending E. M. Forster’s lecture called the Aspects of the Novel that he delivered at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1927 –– a time when the university had no female undergraduates yet.

It’s possible to put down a novel (face-down) on the carpet. To leave it there and forget about it.

To attend to all manner of other things and make it wait.

Kate Briggs

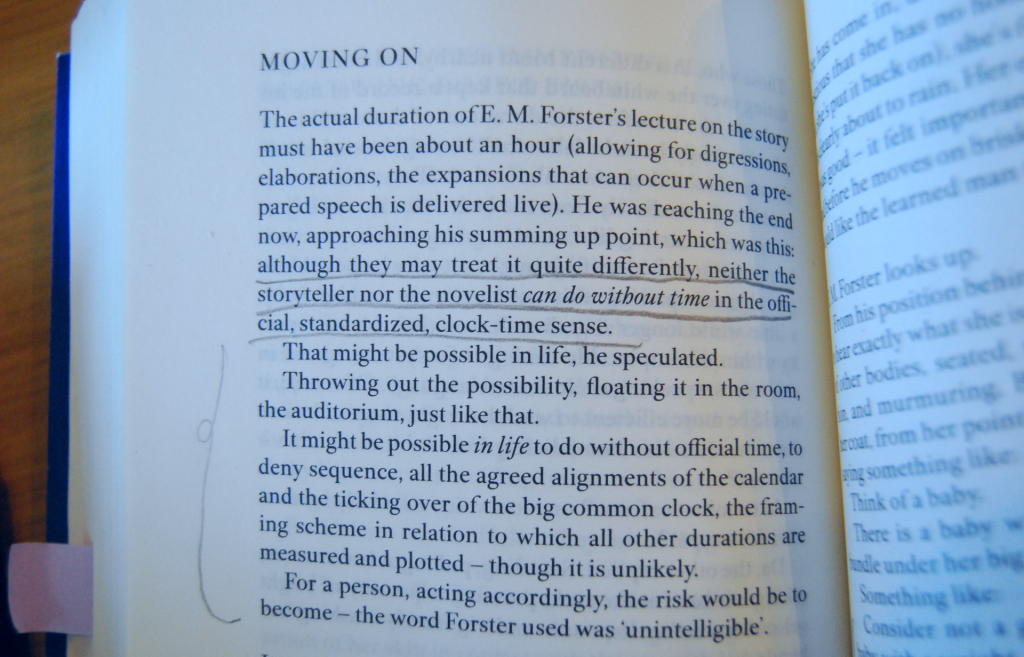

Forster argued that daily life is always composed of two lives: one defined by clock-time –– the relentless marching on –– and another driven by values, which causes time to stretch, slow down, accelerate, shrink, or expand. (Briggs 283) He also believed that novels come closest to imitating real life, because novels are equally interested in the lived experience of time, while also being bound to the inevitable marching on of time. He speculated that throwing out the standardised clock-time might be possible in real life, but anyone attempting to do so, would risk becoming ‘unintelligible.’ (Briggs 296)

At this point of the lecture, Helen finds herself interrupting E. M. Forster. It becomes clear to her why she was listening in on it in the first place: It’s to say that Rose –– and babies in general –– don’t know time. She categorically refuses to submit to organised, collective, ‘official’ time. Helen argues that Rose, and just like everyone else, was born “radically oblivious to the common rhythm-consensus that ‘dinner comes after breakfast,’ or ‘Tuesday after Monday.’” (Briggs 298) The rhythms of the calendar and clock-time are something that we acquire if it’s not straight-up violently imposed on us. (Briggs 304)

Helen, too, used to enjoy the rhythms dictated by the clock. She used to love the quiet of the mornings, her morning coffee gradually being replaced with tea as the day went on. Bedtimes. The oppressive nine-ish-to-six-ish of her office job. The regularity of the alarm clock. But becoming a mother stripped her of this familiar rhythm, forcing her to embrace a new time scheme, which is patternless and driven by the non-rhythm of someone else. Because, as Briggs writes, “Rose SMASHES time! She fucking smashes it.” (303)

Arguably, Briggs does not only reveal the various temporal structures and spheres a novel can operate in but also exposes the private histories of mothers. That they are abruptly taken out of the rhythm that collective time dictates and are forced to learn a new mode of time, a new mode of being. Dinner is not always followed by breakfast, and bedtime is not a sanctuary anymore. Time is measured by its intensity, and “some moments, hours, days last longer than others.” (283)

The Long Form invites us to experience a piece of this private history of mothers –– a history that’s been simplified and skipped over for centuries on the account of being too domestic, too uninteresting, and not concerned with public affairs. However, we all have private histories, and I dare to say that our private histories often have more in common than our public ones, which are often shaped by competing interests and narratives.

Because, similar to Helen, we all have experienced being too tired, waiting for nothing to happen, or hoping that nothing will happen. And if we are lucky, we have all experienced time stretching on, expanding, and quickly shrinking again while waiting for the kettle to boil for an afternoon or bedtime tea.

By capturing these details of life that happen off stage, the ones that unfold within private spaces, The Long Form creates a sense of closeness between the readers and the characters. We are no longer distant observers but are entrusted to enter a private sphere and be in communion with the characters. We are trusted that we will understand, that we will get it because of our shared humanness, because of our shared private histories.

This closeness made me feel like I was a part of this novel, fully embraced by its rhythms and non-rhythms. I find myself reaching for it, recalling it, and entering its realm over and over again, letting the narrative thicken and intensify. Letting it fold and unfold every time I pick it up. The Long Form –– part novel, part meditation on the novel itself –– is a book for me. It spoke to me. And I hope that it will speak to you too.

Briggs, Kate. The Long Form. Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2023.